How Satellites Put a Better Wine in Your Glass

Sponsored By

“Wine is nature’s magical accident,” wrote former champion jockey and mystery writer Dick Francis. We enjoy wine today because naturally occurring yeast on grapes turns the sugar within them into alcohol. For centuries, vineyard owners and winemaker have done their part, but for wine-lovers everywhere, the unsung hero is nature.

Growing grapes for wine depends on a deep and intimate knowledge of what the French call the terroir (ter-WAH): how the region’s soil, climate and terrain affect the taste of the grapes grown there and the quality of the wine. Terroir is one reason that the regions of Burgundy in France, Mendoza in Argentina, Tamar Valley in Australia and Napa Valley in America produce distinctly different wines that compete on the global stage.

The Right Amount of Vigor

Such methods work well for the small, family-owned vineyards that have dominated the trade throughout history. They are an increasingly poor fit, however, for the global business that wine has become. More than one million wine producers around the world bottle and ship close to 3 billion cases per year. Forty percent is for export, and world trade in wine generated $30 billion in 2012 alone, with the US and China being the two biggest importers. The “new world” vineyards of the US, South America, South Africa and Australia in particular cannot afford to build understanding of their terroir through centuries of trial and error. They want to profit now from serving a thirsty world – and have turned to a combination of satellite and information technology called “precision viticulture” to do it.

Eyes in the Sky

Two space-based technologies underlie precision viticulture: satellite imaging and global positioning by satellite, better known as GPS.

Winemakers use photographs captured and transmitted by satellites in orbit and enter them into geographic information system (GIS) software to generate detailed vineyard maps. The images are sharp enough to let the entire vineyard be divided into 2-meter square blocks, and the software is capable of recording not just elevation and slope but the different soil conditions such as acidity, clay content and water retention ability for each block. It still requires walking the vineyard to gather that information, but the result is a digital asset of enormous value in getting the most from the land. Using it, winegrowers can determine the best grape, plant spacing, arrangement of rows and irrigation or drainage for each 2-meter block.

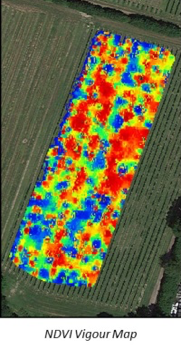

But photographs in visible light are just the start. Infrared detection from space can reveal much more. Specialized satellites beam infrared light at the ground and receive reflections. These can be analyzed to produce something called a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), which accurately measures the amount of leaf area in each 2-meter block. By taking repeated scans through the growing season, winegrowers can get a detailed block-by-block analysis of the all-important vigor. They can then focus their attention on blocks where there is too much or too little, and apply the time-honored practices of winegrowing to reduce or increase it. The result is lower labor cost, higher productivity and grapes of a more consistent quality year in and year out.

Pinned to the Ground

Drivers and mobile phone users take GPS for granted these days, but it has also become vital to agriculture. It is the GPS coordinates that pin the satellite images to specific locations on Earth, block by 2-meter block, making what would otherwise be nice pictures into useful information. For larger vineyards, GPS and GIS systems are also used to steer mechanized pruning, watering and harvesting machines. These systems are not cheap, but when vineyards operate on a big enough scale, they reduce costs and waste while improving quality.

The world’s production of new wine has been in decline since 2004, when the total amount of wine produced surged to its highest level in 40 years. That has, paradoxically, been good for the long-term health of the industry, because growth in consumption has slowly taken up the excess supply. The world now faces a major undersupply of wine production, according to a 2013 report by Morgan Stanley. In the past ten years, satellite and information technology have allowed growers to reduce costs and make their operations more competitive. With the market turning up across much of the world, the future looks bright for those growing and making wine, as well as those enjoying the results of nature’s magical accident.

Sources: “The Digital Grape,” by David R. Green, Fine Wine, March 19, 2012. “Satellite Technology Helping to Produce the Perfect Grape,” by Laurissa Smith, ABC Rural, July 6, 2015. “How to Create a Perfect Vineyard: Buy a GPS,” by Jamie Goode, The Guardian, July 13, 2014. “The Global Wine Industry: Slowly Moving from Balance to Shortage,” Morgan Stanley, October 22, 2013.